no free-will

Choice and free-will continue to be (mis)used to suggest we have a degree of autonomy, along with the freedom to choose any option we are presented with. But they are completely delusional explanations for how we make decisions.

We are just programmable organisms. It is the substance of that programming that determines what we think and believe, and therefore what we do.

Free-will is commonly understood as the ability to make choices and take actions without being constrained by external forces or prior events. Or more simply, the ability to decide what to do independently of any outside influences. The question at the heart of the free-will debate is whether we can transcend the deterministic nature of how everything else in the universe – both organic and inorganic – is governed?* The fact that there is a debate at all, is simply because we have not been prepared to accept that who we each are is nothing more than the sum of the genetic, environmental, and social influences that fashion who we each become. There are no other elements in the equation that determine what we ‘choose’ to do.

*Randomness is a feature of the subatomic realm, and some philosophers have naively seen this as a possible challenge to determinism, uncomfortably suggesting that this ‘contradiction’ offers us the wiggle-room to have free-will, a connection that is a contradiction in itself, as free-will is supposedly anything but random.

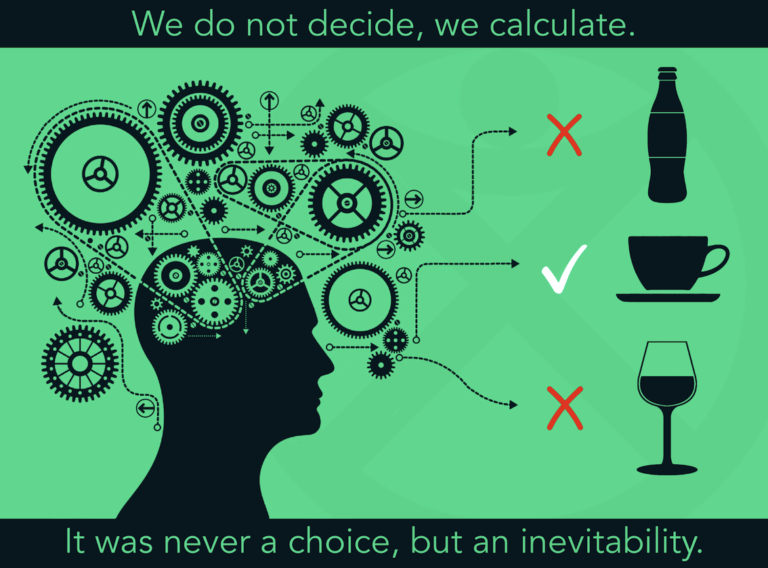

In any given situation where someone has to make a decision, replace decide with calculate. Calculating, in this context, is the process by which a person evaluates that particular situation with a view to establishing the most appropriate action to take. However, they are unavoidably constrained by their unique set of conditions; that of their current needs, desires, motivations, moral values, beliefs, biases, and past experiences – all filtered through their subjective assessment of the possible consequences, and a consideration for the effects of external influences at that moment.

The conclusion to that process is wholly dependent on all those pre-existing parameters and the current situation – there are no other factors involved – and therefore it was never a choice, but an inevitability. That process by which we evaluate the situation we find ourselves in, with the motivations we are trying to satisfy, through the lens of our limitations and prejudices, determine what we do. Not referring to those underlying conditions would result in an arbitrary outcome, which, by definition, is not a choice. And significantly, those ‘conditions’ are all received influences, whether through our genes, education, experiences, or environment. They are the ingredients that make us who we are, and they ultimately are responsible for what we decide to do.

The idea of choice arises because we are aware of the possible options that present themselves when calculating which one is best for us at that time. But what we’re not fully aware of, or indeed unaware of, are the neurological processes involved in calculating which option is deemed most appropriate for us. To further support the illusion choice, we might retrospectively think that we could (or should) have taken one of the other options, but that understanding is influenced by the consequences of having responded to that initial calculation – information that was not previously available.

That calculation is going to be a combination of subconscious and conscious processing. The latter does not infer control, rather, that the subject is aware of some aspects of the calculation, and therefore will have, to some degree, an understanding of why they executed a particular action.

“Why did you do that?” The fact that there are reasons that can be referenced when explaining an action, further demonstrates that the action was not a choice, but a consequence of those reasons. Since we each have a unique set of conditions that determine our own actions, it also explains why people often respond differently in the same situation, and it is those varied responses which also reinforce that illusion of choice.

You are in a scenario where you are offered a drink; a choice of coke, coffee, or a glass of wine. Other options also become available; you could, for example, decline to have one, or you might ask to have a glass of water instead. It’s mid-morning, you’ll be driving later on, and so you don’t want the wine. Aware of the issues relating to a high sugar intake, you always avoid coke and similar drinks. Yet you feel compelled to accept the hospitality because you calculate that it would be beneficial for you to do so on this occasion.

Noticing that your host already has a coffee, and not wishing to put them out, and since it’s also a little chilly this morning, the offer of coffee seems to be the best option to satisfy all those considerations. The question is whether you ‘deciding’ to have coffee was a free choice, or was it inevitable?

Every decision we make can be explained because there are reasons that direct the outcome. Being aware of that process does not mean that we are free to act independently of those determinants.

The mistake we make is assuming that those aspects of the decision-making process we’re aware of must belong to an independent ‘self’ – an internal director pulling the strings. But if such a self existed, it too would be subject to the same constraints that shape all behaviour: our biases, beliefs, preferences, motivations, and experiences. And so the outcome would be no different. However, if this director were somehow free of those constraints, its choices would be unrelated to the very person it claims to represent.

We are not some independent entity within our brains, but the sum of our subjective influences – our evosocionetics; genes, received beliefs, education, experiences, social conditioning. We can never be free of those determinants, because they define who we are, but they can be modified through other influences, new education, and ongoing experiences, which are the mechanisms that allow us to change.

The argument that we can function without referring to those pre-existing conditions, or to the situation we find ourselves in, and then decide to do something without any motivation as an attempt to demonstrate that free-will is possible, is clutching at straws. It is not an expression of free-will, just a demonstration of doing something for no apparent reason. That, in its own right, is the reason for doing it, so again, it is not free. There is always a ‘because of’ behind everything we do – it is unavoidable.

So the inclusion of ‘free’, in ‘free-will’, is there to suggest autonomy, when really we should simply talk of having ‘will’ (motivation, purpose), something which is wholly consequential of everything but ourselves.

To talk of free-will, then, is to misunderstand both the nature of causality and the construction of the self. What we call choice is the consequence of countless conditions. And what we call the self is the accumulation of those conditions over time.

Humans believe they are free simply because they are conscious of their actions, but ignorant of the causes that determine them. Spinoza 1632 – 1677

purpose

Humans have recently developed an extraordinary gift for missing the obvious. Our endless search for ‘the meaning of life’ says less about life and more about us – our vanity, our arrogance, our refusal to accept that we’re not the centre of everything.

We ask, “What is the meaning of life?” But life does not need to justify itself. Its purpose has always been clear: adapt, survive, reproduce, and repeat, so it can weave itself into the complex interdependencies that sustain everything from forests to coral reefs to the breath in our lungs.

But in this latter part of our evolutionary journey, we decided that wasn’t enough. So we invented new purposes; ambition, wealth, progress, legacy, indulgence, even imagining an after-life. We began to live as if we weren’t life at all, but something superior to it. Something entitled to exploit the planet to satisfy those abstract goals. And now the planet is breaking under the weight of that delusion.

We behave as if we exist independently from the ecosystems that created us, as if the rest of life itself is expendable in pursuit of our own selfish ends. But we are neither separate nor exempt. We are an inextricable feature of life, and life has rules.

So let’s stop pretending there’s some higher meaning waiting to be found in technology, through personal indulgence, or the false promises of religion. If we reject the raw, unsentimental logic that allows life to thrive – the force which brought us here – we reject the only thing that makes our own existence possible.

There is no greater purpose than life itself. Life is the meaning of life. Either we remember that, or we won’t be here to forget it.

March 2023