rent or wrong?

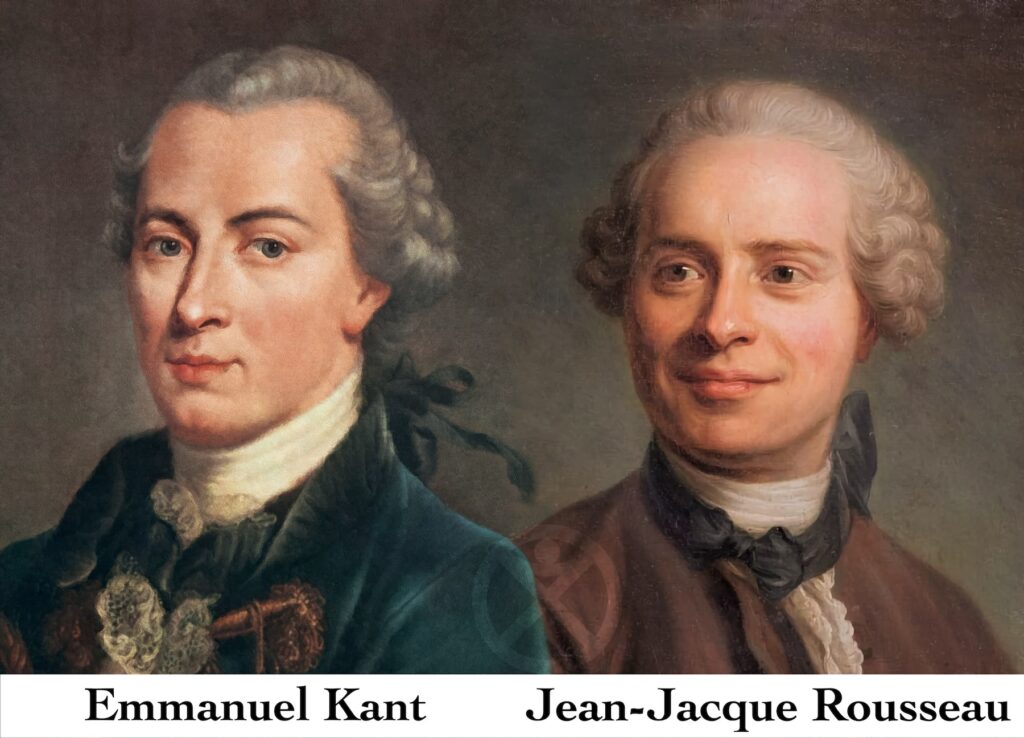

The Age Of Enlightenment (also known as the age of reason) is a period in history covering the whole of the eighteenth century. It was a time of intellectual and philosophical innovation, using science and reason in the pursuit of human betterment. It is summed up by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant as: Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity.

‘Dare to know! Have the courage to use your reason!’

Jean-Jacque Rousseau was an Enlightenment philosopher, born in 1712. One of his central ideas is that we humans are naturally good, and that it is society that corrupts us. He saw that the real problems were the political systems and social conventions which were designed to restrict people’s freedoms (including the freedom of thought), and to preserve the structures which were the cause of inequity within society.

Nearly three hundred years later and that same social structure that is weighted in favour of the privileged hasn’t changed, other than the extent to which that inequity now exists between the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’. One key mindset that requires re-examination is our acceptance of ownership and the injustices and exploitation it levies on the less privileged. Rousseau recognised this corruption, and offered the following summation:

The first man, having enclosed a piece of ground and saying, “This is mine”, and having found people naive enough to believe him, was the real founder of civil* society. From how many crimes, wars, and murders, from how many horrors and injustices might someone have saved mankind, by pulling up the fence posts and crying to his fellows, “Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.”

*’Civil’ in this context, does not mean civilised, but refers to the protectionist foundation of society’s legal framework that preserves the rights of the privileged – those who own land and property – to not only exploit the poor and vulnerable, but also all other species and the natural world with impunity.

The normalisation of renting as a means of property-based exploitation is rarely questioned – either ethically or morally. Despite the clarity and weight of the above observation by Rousseau regarding land ownership, we are not taught that for the vast majority of the 160,000 years since the emergence of modern humans, shelter was shared, not sold. The idea that one individual could hoard homes while others had none would have seemed both absurd and indefensible to our early ancestors. Cooperation, generosity, and mutual care were not abstract ideals – they were essential for survival.

In a truly human society – human as in naturally egalitarian and pre-civilised – offering someone shelter would never have come with a price tag, let alone the threat of destitution for failing to pay. The idea of saying, ‘You may sleep here, but only if you surrender most of your labour to me,’ would have been met with derision. And rightly so.

Yet today, property rental is an established investment opportunity, protected by law, and treated as a measure of success. Using privilege to extract the proceeds of another’s labour continues unchallenged – even though it leaves vast numbers of people disadvantaged, if not impoverished, and deepens the destructive divide between rich and poor.

By critically examining the system that perpetuates housing inequality, we can begin to imagine a different kind of world – one in which rent no longer exists, because it is understood as fundamentally immoral. After all, what gives anyone the right to claim ownership over land they do not need, and then demand that others hand over their hard-earned income in exchange for the basic human requirement for shelter – something no human should be denied? This example of economic servitude is a quiet, legalised form of modern slavery, disguised as normality.

Creating a more equitable system means not only ensuring universal access to safe, affordable, and dignified housing, it requires rethinking the cultural assumptions we’ve inherited: that property equals profit, that wealth implies virtue, and that passive income is a just reward, rather than being the unearned gains of exploitation, and the abuse of privilege.

April 2024