sport is war

…and war is sport for those who rule

‘panem et circenses’ – Juvenal A.D.100

Give them food and sport…..(and they will be compliant.)

Sport is a spectacle of control, no different from the bread-and-circuses strategy employed by the rulers of Ancient Rome, one designed to distract and pacify the people rather than to encourage intellectual development and community engagement – a strategy that is even more pervasive today, woven into the very fabric of society through relentless media coverage, nationalistic pride, and vast financial investment. It dominates our culture, our conversations, and even our education systems, ensuring that competition, allegiance, and hyped-up drama take precedence over critical thought and collective progress.

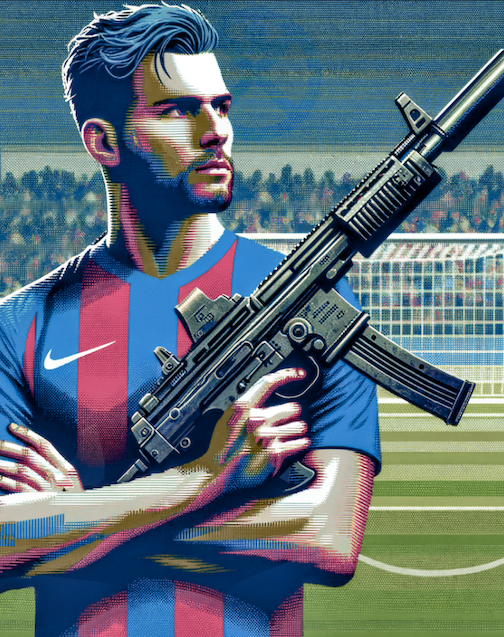

Sport is so basic that even a two-year-old can easily understand the rules of the game. And yet, this formula is only a step away from war: take sides, embrace aggression, defeat the other, and claim the spoils. This is why sport is so heavily emphasised – it trains the mind for conflict, ensuring that when the time comes, the raw instincts required for us to fight are well primed.

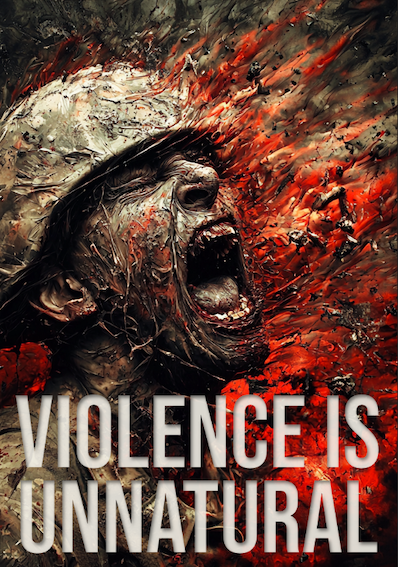

But in glorifying war and sport, we suppress the very faculties that once gave us our greatest advantage; empathy, collaboration, kindness, egalitarianism, and an evolved moral understanding that it is wrong to harm another. Those in power do not want a thoughtful, cooperative populace; they need one ready for war, unquestioning in its obedience, and eager to fight. And so, this deliberate suppression of human intellect, in addition to an ongoing diet of violence in all other forms of entertainment, instills in us the belief that there is righteousness in killing for a cause, and honour in falling for a flag – the justification for war.

It is against our evolved nature to harm another, let alone justify it through state sponsorship. If we think violence is acceptable, in any form, we have already been dehumanised.

Life is such an incredible experience, and yet, to think we evolved with such profound intelligence, compassion and understanding, only for that to be replaced with a bloodlust for inflicting pain, death, and suffering onto others – is the darkest tragedy of civilisation.

There is no absolute definition that describes ‘what it means to be human’, as the ongoing debates in anthropology, behavioural sciences, and evolutionary biology demonstrate. Attempts to define humanity by studying indigenous tribes, archeological remains, comparative cultures, or our genetic lineage, can be misleading; in truth we are the products of circumstance – creatures moulded by the unique conditions and demands of our specific environments. As a consequence, the full spectrum of human potential is rarely, if ever, realised, unavoidably creating a diversity in behaviour, values, and social structures, none of which can claim to be the definitive representation of humanity.

To compound the limitations of those environmental influences, throughout our recent ‘civilised’ history, that latent potential has been deliberately repressed, to the point where our contemporary understanding of ourselves is but a degraded version of what we might otherwise be. Unfortunately, it is this crude impression that persists in being the measure by which we now define ‘human’.

Our civilised history, as documented by the relentless acts of violence, persecution, and hatred we inflict upon one another, supports the impression that we are, by default, violent creatures. Yet it is our leaders – those who manage our beliefs and values, and command our loyalty – who fuel our hostility, and direct us into the conflicts we are forced to endure, all because it serves their own ambitions. We have come to accept this manipulation as a natural aspect of our common identity, as if warfare were simply a reflection of what it means to be human. That is irrefutably wrong; the same dog can be trained to be the most loveable companion, or a vicious beast, it just depends on the designs of whoever is in charge of that training. We are no different in how we are fashioned to think and behave, and what we accept as ‘normal’ by those who take ownership of our development.

From a young age, we are taught to compete for attention, acceptance, and rewards. Sport plays a major role in that early conditioning, promoting two very simple ideas: firstly, the binary concept of two teams (or individuals) competing to achieve a simple task better the other. And secondly, as spectators, we are expected to take sides – ‘which team do you support?’ These reinforce the main societal constructs of competition and allegiance – the essential ingredients of war. This persistent trope of ‘us against them’, ‘good versus evil’, is further instilled through our entertainment; from religious texts to the gladiatorial arena, from films to video games, where heroes defeat villains with weapons and violence. These influences shape our worldview, making us believe that enemies and conflicts are inescapable, and that we must align ourselves with identifiable groups – be it through nationhood, religion, history, race, or social class – and see other groups as potential enemies. These identifiers are the abstract inventions of those in charge, designed with the explicit intention of fuelling animosity by demonising those other groups – the catalyst for war.

Even in conversation, we mirror the same competitive dynamic, treating differing opinions as challenges that need to be defended, and those that we agree with, we use to prop up our inherently limited perspectives. Discussions turn into arguments – battles to be won – because we do not have the imagination to think beyond this bigoted attitude.

Sport has long mirrored warfare, with teams of players resembling soldiers in uniform, marching onto the field of battle. Many sports, like wrestling, fencing, javelin, and archery, have their roots in combat training. Even the symbols of victory, in the form of medals and trophies, are drawn directly from military traditions, tokens to celebrate the ‘glory’ of war in front of loyal, beholden supporters.

The connection between sport and war is not in any doubt, but competition extends beyond sporting prowess. It is ingrained in every aspect of society; politics, business, academia, industry, and even entertainment, where music, dancing, and even baking, have turned creativity into a contest. This childish, competitive mentality, driven by ego, reward, and the prospect of status and/or fame, has become so normalised that it is no surprise that we assume it reflects our intrinsic character.

It begs the question; should we continue to promote and celebrate ego and competition – immature expressions of our primitive instincts, which foster selfishness, aggression, and division – when it is these very motivations which have led us to the brink of our own extinction? Surely it’s time to elevate ourselves from this contrived rudimentary state, and return to one that is centred on collaboration, compassion, imagination, and care – those unique, nature-given faculties which evolved to afford us significant benefits over the primitive impulses that our current system is determined to prioritise – at our expense.

The ongoing emphasis on sport and competition, the investment in military strength and war, and the acceptance of violence as the primary narrative of our entertainment, is why we have denied ourselves a future.

This is not our world, it is the world, a unique planet where we, as visitors, evolved with the intelligence to recognise how astonishing the existence of life truly is. We have the capacity to protect and preserve this once-in-a-universe phenomenon, yet we also wield the power to destroy it. The very force that affords us this privileged perspective is the same force that keeps us alive – so if we want to continue to witness and experience life, why do we allow those in charge to pursue their wilful destruction of that which we need to survive?

Our unrelenting commitment to military power as a primary tenet of geostrategy is driving the world towards a prolonged and catastrophic war. As habitable and arable land become increasingly scarce and the global population rises, mass migration will escalate, triggering a desperate struggle for dwindling resources – resources we recklessly squander in our obsession with technology and overconsumption. Nations will continue to increase military investment, justifying the subsequent mass destruction as a demonstration of their blind faith in ‘might is right.’ This final display of arrogance and ignorance will persist until nothing remains. We stand on the precipice of this reality. The only alternative – the only rational path to survival – is to abandon the values, beliefs, and illusions that have brought us to this point. Instead of being victims of the selfish ambitions of a deluded, but powerful, minority, we must construct a society founded on the preservation of all life – one guided by the sum of our collective knowledge rather than being propelled into obscurity by the crude instincts of greed and power.

Jan 2025